My return to San Francisco had been scheduled on March 17th. The date was arbitrary in selection, but proved significant because that’s when the Bay Area officially began to shelter-in-place — an order that remains today and for at least a few more weeks. A few days before that, the US government restricted travel back from much of Europe, which didn’t include Turkey, possibly to the chagrin of the western half of Istanbul and the coastline I had been exploring, where Greek islands are a 30 minute ferry ride away. With US airport border crossings clogged for hours by hoards of travelers trying to clear customs before the deadline, I pushed back my return flight to avoid the frenetic crowds and started practicing my Turkish.

Thus began an indefinite waiting period where I watched the global mayhem unfold from an overseas vantage point. I’m not a stranger to forced isolation in this nature — I used to drive nuclear submarines as an officer in the US Navy. During a deployment to the Arctic Ocean in early 2011, my submarine received an ominous transmission that I’ll never forget: Nuclear Meltdown in Japan. The headline, which was all that low-bandwidth polar satellites could process, referred to the disaster at Fukushima Daiichi power plant in the wake of the earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Gripped with suspense as only nuclear engineers would be, my fellow officers and I extrapolated the possibilities of the short text to determine if we should be rendering assistance in some way. Alas we couldn’t abort our mission to the North Pole and would have to continue tracking developments from the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl from a steel tube that was thousands of miles away under the ice cap.

Watching the initial pandemic response and the compounding economic disaster play out from Turkey was decidedly different than from a submarine or my one-bedroom apartment near Golden Gate Park. Of course, Turkey was also dealing with the crisis, having directed closures for all but essential business and schools, restricting congregational prayer, and implementing rolling curfews on the weekends—preventing over 80 million people from leaving their homes except in an emergency. People with underlying conditions deemed a high-risk and those over 65 were prohibited from being out and were deterred with a hefty fine, as were those under 20, who apparently continued to flaunt immortality. I kept to the garden, went for periodic walks, and took a few short trips to explore other villages and to learn from my host how to select the right species of locally-caught fish. While US supermarkets exhausted critical supplies and supply chains were put under buckling pressure, the bazaar never ran out of the freshest tomatoes, artichokes, and honey I have ever seen. Liters of homemade olive oil was still delivered to our house each week to meet the steady demand and there was never a shortage of toilet paper (bidets are built into every toilet).

While I was growing accustomed to life in Turkey, the US Embassy sent daily emails with health updates and travel advisories to US Citizens and green card holders who remained abroad. Once Turkish Airlines grounded all of its flights, the commercial travel options back to the states became extremely limited. Forced to consider routes through Belarus or Qatar—layovers I wanted to avoid regardless of duration—I resolved that my well-fed and well-isolated conditions were better than risking exposure on a complicated itinerary just to quarantine in my one bedroom apartment in San Francisco. Channeling my inner submariner lurking under the waves, I would stay in Turkey and continue to monitor the response back home for the right time to surface.

As masks became a daily habit and plexiglass barriers were erected in grocery stores the world over, curves began to flatten signaling that extreme measures are good for public health even if they devastate the global economy. Recognizing the desire for travel that avoided multiple lengthy layovers, the US State Department compelled Turkish airlines to reanimate flight crews and coordinate airport personnel to service direct flights to New York, Washington DC, and Los Angeles in the last week of April. With the continuation of rolling curfews and the month of Ramadan coming, the Embassy strongly urged immediate repatriation. The officials were making it clear that this evacuation would be the only near-term option, otherwise I’d have to remain in Turkey until the end of May, at the earliest, possibly longer. I bought a ticket on Tuesday for the evacuation flight on Thursday at 2 a.m.

Attempting international travel during a pandemic meant a lot of logistics had to come together quickly. Since the borders between provinces were closed and the flight was scheduled during a 4-day curfew, I needed to obtain a travel permit from the Turkish police that I would present at a dozen health checkpoints along the 300 mile drive from Izmir to Istanbul where I’d catch the plane.

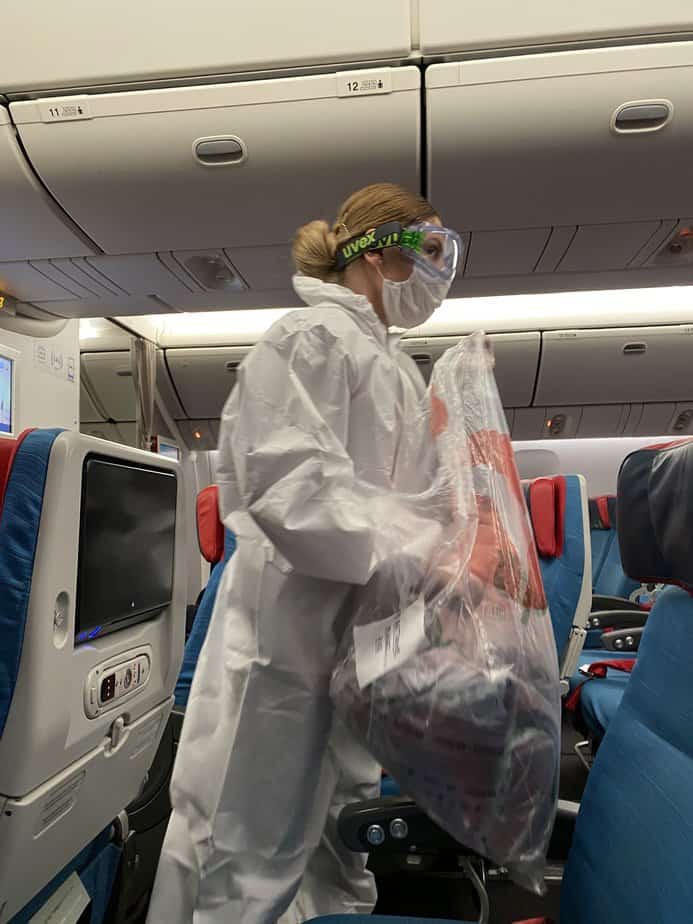

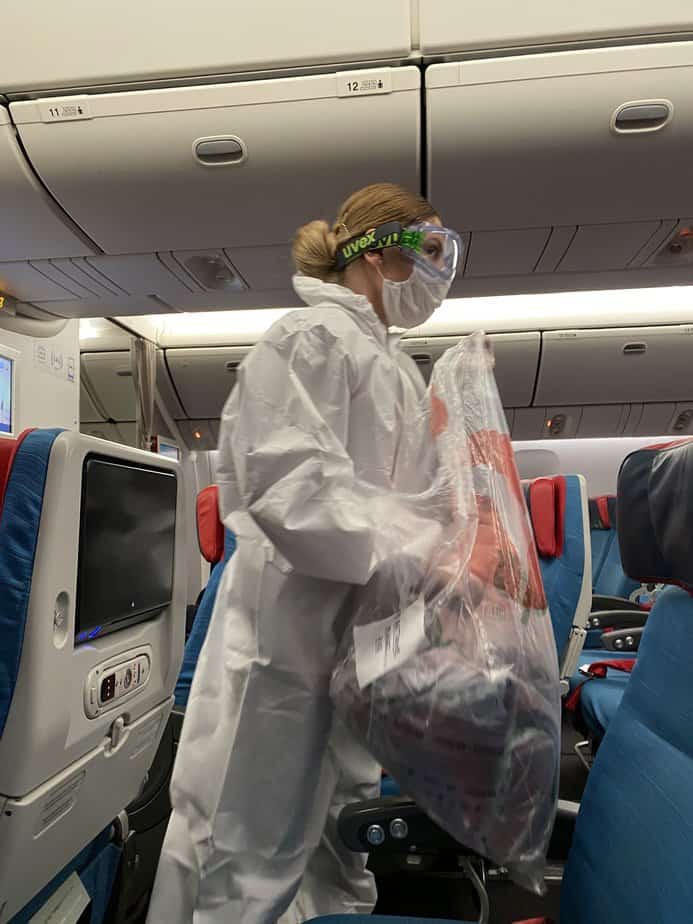

It’s hard to grasp how shut down the world is until you are really out in it—beyond the grocery store. The Istanbul airport (one of the world’s largest) was almost entirely abandoned and only those with a ticket could enter after getting a temperature check. The grand concourse, which usually boasts high-fashion boutiques like Gucci, Hermes, and Bottega Veneta, was in mothballs. The duty free shop was laid up and preserved in plastic and a solitary çay stand and pharmacy were the only remnants of commerce. The few emergency personnel there for security, health screening, and flight operations were wearing masks and gloves. Any employees that were flying in the plane or working with luggage were additionally wearing hazmat suits and ski goggles. Every passenger had their own row for the 14-hour flight and individually-wrapped food was served in a plastic bag that said “We Will Succeed Together”.

It’s been almost a week since I returned to self-quarantine in the Bay Area to a more cramped, less convenient, and unquestionably more tense vibe than in Turkey. The queue outside the grocery stores and parks jammed with people in the middle of the “work day” has me wondering where an American city — especially one that was already suffering from an affordability crisis, extreme wealth inequality, rampant homelessness, and crumbling infrastructure — goes from here. Does the housing market crash or will renting a one bedroom apartment cost more than the majority of Americans make in a year? Will we embrace localism or continue to demand just-in-time deliveries via complex supply chains that easily break? Will we reject an expansion of the surveillance state or continue apathetically trusting far-reaching tech conglomerates to safeguard our personal data?

As we learn to live with the virus for the foreseeable future, it’s never been more important where you decide to reside and how local officials guide your return to normalcy. As I continue to isolate myself in a 400 square foot apartment, dreading a return to Whole Foods, I can’t help but wish I was getting kilos of fresh produce at the bazaar and tending the garden. By now, I probably would have been able to swim in the Aegean, too.

// Photography by Ekin Balcıoğlu. Balcıoğlu s a visual artist with nearly 15 years of creative experience. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in New York, San Francisco Bay Area, London, Istanbul, Izmir, Ankara, and Sofia. She received her BA (Honors) from Central Saint Martins and a MA/MFA in Visual and Critical Studies and Fine Arts at the California College of the Arts.